Italian Bible History

The Italian Bible had some early success at the printing press. Italian was the third language in which the Bible was printed. In 1471, two Italian Bibles were being prepared simultaneously. A Venetian scholar named Nicolo Malermi’s translation of the Latin Vulgate was finished first in August. Then in October, an anonymous edition was made, which used manuscript Italian and in the later stages also considered the recently printed Malermi Bible. The latter was only printed once; however, Malermi’s edition was reprinted some 12 times over the next 60 years without competition. In 1530, the Florentine Antonio Brucioli’s Italian New Testament translation from the Greek was printed and in 1532, his translation of the whole Bible. Pietro Aretino wrote to him in 1537, noting Brucioli’s intelligence in Hebrew, Greek, Latin and Chaldean. Both Brucioli and Malermi’s works were printed into the early second half of the 1500’s. Brucioli’s work was also quickly revised by a couple of Dominican friars, who printed it under their own names. Fra Zaccheria da Firenze edited Brucioli’s New Testament and had it printed in 1536. Santi Marmochino slightly edited Burcioli’s Old Testament with the addition of some Vulgate readings, joined it with Fra Zaccheria’s New Testament, and printed the whole Bible in 1538. In 1551, the New Testament was printed, which was edited by a Florentine Benedictine monk named Massimo Theofilo. He used Brucioli’s New Testament and revised it using some of Malermi’s work and some of Fra Zaccheria’s. Then in 1545, an anonymous revision of Brucioli’s New Testament was printed by “al segno de la Speranza”. In 1555, an anonymous revision of the New Testament was printed by Crespin in Geneva. The first Italian scripture to have verse divisions was done by Giovan Luigi Paschale in 1555. He printed Crespin’s text of the New Testament parallel with the French text. He later went to Southern Italy and was martyred for the faith. Theodore Beza had a hand in the revision of Crespin’s text in 1560. In 1562, Brucioli’s Old Testament was edited and printed in two different editions, one of which included the 1560 Crespin New Testament and another which included a heavily revised edition of Theofilo’s New Testament. A quick look at the book of Romans can help decipher the two editions. In the latter, the heading to the book of Romans errantly reads “Acts”. Both of these New Testaments were printed, without revision, one more time before the 1600s.

The Council of Trent took place in the latter half of the 1500s and all but killed the Italian Bible. Mattia d’Erberg elegantly describes the situation in the early 1700s: “If European languages, invited to the wedding feast of their Bridegroom, can pride themselves on delicious and exquisite treats reserved for them from each verse of the Scriptures, only the Italian language (however rich compared to the others) could have cause to complain that she had nothing but narrow bread and little water. The reason for this is the extreme rarity of the Word of God imprinted on their vernacular.” Around 1743, Giovan Gotlobbe Glicchio said he had spent three years in Italy and had not seen a single copy of the Scriptures in Italian.

The Italian New Testament and entire Bible were printed more than 60 times in the 1500s. In the next 100 years, only two Italian New Testaments and two whole Bibles were printed, and all of them were the work of one man. In September of 1541, King Charles V of Italy and Pope Paul III were meeting in Lucca, Italy, to discuss the religious quarrels in Germany and some other political matters. King Charles V was awoken to a disturbance on the night of September 17. In the morning, he found out that a noble lady had given birth to a son. Charles offered to be the godfather, and the Pope baptized the child. The King’s name was given to the baby, Charles Diodati.

In Lucca, the Diodati family became favorable to the Reformation through the work of some preachers, including Peter Martyr Vermigli, whose ministry in Lucca was brief but enduring. At the beginning of 1567, Charles and several other families fled Lucca, searching for freedom to worship God as they thought was right. Charles ended up over the Alps in Geneva, Switzerland. In early June of 1576, his second wife gave birth to his third son. They named him John.

Giovanni Diodati

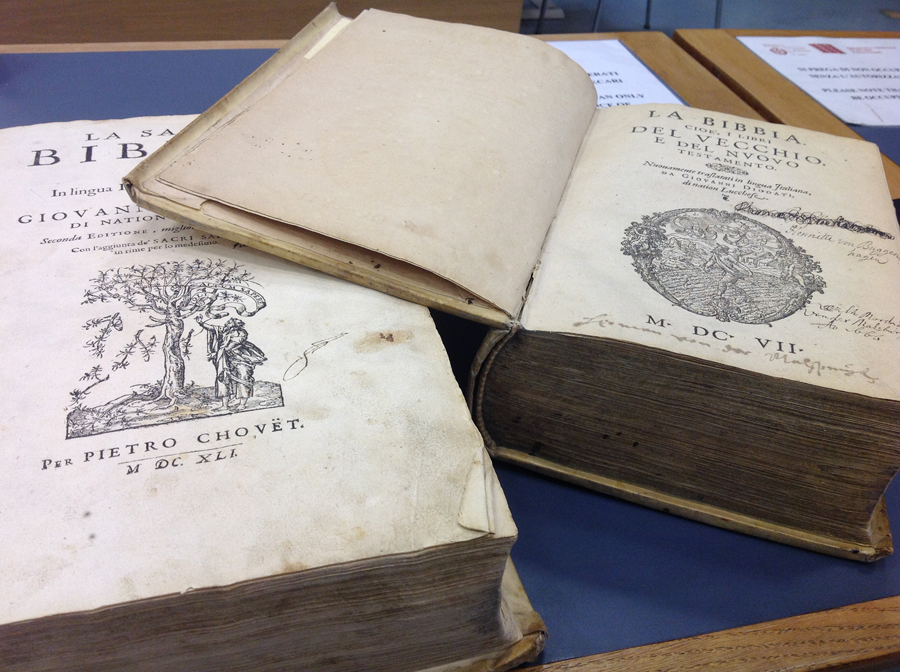

The Italian Bible was last printed 14 years before the birth of John Diodati, and it would have to wait another 31 years until he printed his first edition in 1607. John Diodati grew up in a French speaking town with a sizable Italian community and an Italian church. He attended the Academy of Calvin and graduated in 1596. In 1598, he was asked to teach Hebrew at the academy, and in 1599, he filled the chair of professor of theology. It was in this position that he approached the council of Pastors in 1603 requesting permission to print an Italian Bible. He would later recall, “…the Providence of God having inclined me in the first years of my Theological Profession; yea, and almost from my very Youth upward, to Translate and Explain the Italian Bible…” For whatever reasons, his translation seems to have stalled for several years until he was contacted by Henry Wotton, the English Ambassador in Venice. Venice was in a peculiar situation and on the verge of totally leaving the Catholic faith. Many Protestants in Europe had hoped that they would join the Reformation. In writing to the Earl of Salisbury on May 26, 1606, Wotton said, “The State useth me with much kindness, and I protest unto your Lordship I think hereafter they will come nearer unto his Majesty, not only in civil friendship but even in religion. I have, upon the inclination of things that way, begun to take order for an Italian preacher from Geneva whatsoever it cost me, out of shame that in this kind, the disseminators of untruth do bear from us the praise of diligence….”

Diodati got his translation ready and put it to print in the summer of 1607. On August 11, 1607, Diodati sent a copy of his Bible with this note to Joseph Scaligero, “I am not without hope of effecting the entrance and diffusion of copies into Venice, where superstition has already sustained a breach, through which liberty has entered, which God will sanctify with His truth when the time is come.” In the spring of 1608, Diodati printed a small New Testament again for use in Venice, “On the advice of the Ambassador of England, who is there I am having the New Testament printed, in a small but very nice format, to support the blessed stirrings that God has made manifest there[Venice].” Two letters written to Duplessis Mornay repeat his reasons for the New Testament: “I also heard from [Wotton] that my version of the New Testament, without notes and in small manageable format, would be of great use and fruit: therefore near spring I undertook the work, and we are in the middle, having very accurately gone over the text, so as not to allow as little as possible errors and harsh and dangerous words. This is being done with so little change from the previous edition that it will be unnoticeable.” And later, “After I had presented my translation of the Bible to the Ambassador of England, who is in Venice, he let me know that my version of the New Testament, separately and in smaller handheld format, without notes, could do much to further the holy cause for which, with great zeal, he is working on there… I sent it to the printer, reviewing it with the most exacting thoroughness that I could, and reducing it to the smallest and most convenient form, and having it printed on quality paper, to favor a trouble free and favorable reception in Italy…” At the end of the summer toward the beginning of the fall of 1608, Diodati took a trip to survey the possibilities of starting a Protestant church in Venice. Unfortunately, he didn’t feel the conditions were ripe. He put a lot of the responsibility on Paolo Sarpi but thought Sarpi didn’t have the zeal to accomplish the tasks necessary. However, he had not given up all hope for Venice, as may be seen by his ordination shortly after returning to Geneva and even more so by the 20 Psalms in rhyme, which he put to press in 1609. The Psalms were printed with the famous Venetian Aldine mark of a dolphin and an anchor, no doubt for their reputation in Venice. For some years, Diodati stayed in Geneva before traveling on several missions into France. Possibly his interactions with the French churches showed him the benefit which a new French translation could have, although he more often claimed that its usefulness would be for the students at the Academy. In 1618, he again approached the Council of Pastors about printing a Bible, but this time in French. At first, the response seemed optimistic, but recent attacks by Catholics against the French Bible would cause the pastors to be cautious of introducing any new French translations. They asked Diodati to suspend his work on April 3, 1618. A few months later, Diodati wrote to his good friend Duplessis Mornay on June 24th, “For a long time now, I have planned and projected to do a revision of our French version that I realized was in several places intolerably deficient, thornily obtuse, and, in short, too much in the style of Junius. I took on the task during my own studies, and if the great obstacle or bugbear of custom and usage do not prevent me from my plan, I will, God willing, all cause for objection from our people, as well as cause for blame by adversaries and I will render the holy writ so easy and plain and agreeable…I have the approval of so many learned and worthy men for my work in Italian. And I have since then thought, reviewed and observed so much that I hope to offer untold amounts of assistance to the students in Theology, who are not helped or interpolated by the marginal notes of our Bibles, I have gone so much further that I cannot go backward now and I would be thankless to do that after the Holy Spirit had guided me and the understanding of the most inaccessible passages so much. I beg of you to explain my intentions to Mr. Portau and others who could risk a lot by printing the Bible according to the previous edition, because if God lends me the time, in a few months I will see my work printed, so that all can judge and then, by the freedom that the church disposes, either admit it into the church for use by all, or leave it for private study…” Soon thereafter Diodati would travel to Holland and be occupied with the famous Synod of Dort for almost a year. Richard Baxter, when describing the Westminster Assembly (1643-1653), said, “as far as I am able to judge by the information of all history of that kind, and by any other evidences left us, the Christian world, since the days of the apostles, had never a synod of more excellent divines than this and the synod of Dort.” Diodati gave his advice throughout the synod and had many opportunities to preach, including his attempt to gather Italians for a weekly service in their native tongue. Diodati was chosen as the representative of the French speaking world to be on the committee which drafted the Canons of Dort. His efforts at the synod have sometimes been criticized, but in some cases, he has been given the title “Champion of Dort.” After the synod, he took a short trip to England where he met King James. Upon returning to Geneva, Diodati continued his efforts to publish his French Bible, which took him a total of 26 years to accomplish. In the meantime, Diodati translated into French Sarpi’s History of the Council of Trent, as well as Edwin Sandy’s Europae Speculum, Or A View or Survey of the State of Religion in the Western Part of the World. He also printed the book of Job in French in 1626, the 25 Italian Psalms in rhyme in 1628, all 150 Italian Psalms in rhyme in 1631, Ecclesiastes and the Song of Solomon in French in 1637, and the French Hagiographes in 1638. March 25, 1639, the Chouet booksellers were fined for selling imperfect Italian Bibles. Chouet’s 1632 catalog seems to be the last one which listed Diodati’s 1607 Italian Bible. By this information, it would appear that they ran out of Italian Bibles, and the Chouet brothers approached Diodati concerning their desire for more copies. Diodati saw the benefit in taking the time away from his efforts on the French translation to further revise his Italian. Another edition of his Italian would help his reputation, plus it would give his critics an opportunity to see a sample of what his French translation would look like. Diodati later wrote to the French Synod of Charenton on November 20, 1644, “…I henceforth took it upon myself to have my Italian version reprinted at great expense and labor, reedited, with additional annotations and completely collated with my French version.” Diodati finished his Bible in late 1640. Most copies bear the date 1641 on the letterpress title page and 1640 on the engraved title page.

In 1640 and 1641, press censorship in England was changing. Doors were opening for the printing of commentary, which the people craved. Printers were rushing to find resources to supply the market’s demand. On November 13, 1641, while Diodati was arguing at the city council in Geneva for the publishing of his French Bible, it was noted, “a great Englishman named Mr. Styl., having represented that his Italian version was filled with very good notes, has given charge to Mr. Gentilis to do the work of translating the Notes into the English language.” In 1643, the first edition of the English translation of Diodati’s notes was printed. In 1645, annotations were put to the press which were authored by the English themselves, wherein they admitted, “We have made speciall use of the Italian Annotations of Deodat, and of the Dutch Bibles.” However the scholars did not say that in some places they simply copied Diodati’s work. Notes from Diodati’s French Bible, as well as notes by Augustin Marlorat, were inserted in the second edition of Diodati’s annotations, which were printed in 1648. The publisher quickly took advantage of the plagiarism by the English scholars.

But the most reall confirmation of their usefulnesse is the high esteem those Reverend Divines (Members of the Assembly) have had hereof, viz. Dr Gouge, Mr Gattaker, Mr Downham, Mr Ley, Mr Reading, Mr Taylor, Mr Pemberton, and Dr Featly, who each of them taking a severall part of the Bible to make Annotations thereon, and printed them together 1645…yet they, I say, all so highly approve of Diodati’s Annotations, that any one who shall please to compare those severall Notes of theirs, with the first Impression of this in English, shall finde many thousands of this our Authours inserted, but especially in Ezekiel, Daniel, and all the minor Prophets, where there is hardly any one Note of Diodati’s forborn, but in theirs printed verbatim by our Translation: which had not their grave Wisdomes found both sound, acute, and pithy, I am confident they would never have made so great use thereof.

The next set of English Annotations were printed in 1651, and the preface was followed by a rebuttal to this accusation, “But to grant this Calumniator as much as in truth can be granted, that one of the Annotators to whose share, Ezekiel, Daniel, and the smaller Prophets fell, hath manifested himself to be Plagiarius; shall his crime be imputed to all the rest…” One mercifully unknown, Mr. Pemberton seems to have been the one responsible for that section of work which included the plagiarism. Their second edition tried to remedy the problem, but in reality, they only added more information onto Pemberton’s work, thereby leaving most of his plagiarism intact. They also overlooked Job, which contained heavy plagiarism similar to that of Mr. Pemberton’s work, as well as the strong similarities in Joshua through Samuel, Acts, and Dr. Featley’s work on Paul’s Epistles. Dr. Featley (the only KJV translator to also participate in the English Annotations) often leaned on Diodati, although it was his Italian that he made use of and not the English translation, which can be seen by his more literal translation.

It was at that meeting on November 13, 1641 where Diodati finally won out and was given permission to print his French translation of the Bible. December 12, 1643, Diodati wrote to Johannes Polyander, “As for me, I praise God that He reserved for my golden years a task so serene and consolatory an occupation that is the edition of my French Bible that follows the Italian one, and how much this second French work, that I bore alone, almost overwhelmed me with a long sickness of six months or more. I am always fortified in our Lord, and I pushed forward with the work so far that by next April it will be published. It will be my fondest desire that your most learned examine and censor it, and that your churches enjoy the fruits of it, if indeed it bear any.” About a month later, Diodati announced that he was finished and wished to have it printed at his own expense, which was accomplished in 1644. It never received official permission from a French synod and did not gain wide popularity. It is my opinion that Diodati wanted to give the world something that would create a lasting fame. He saw that his highly praised Italian Bible was barely used and attempted to leave behind something of much greater use. Only centuries later can we clearly see that it wasn’t his French which made him famous, it was the Italian. His French was only printed that one time, but his 1641 Italian later became the standard Italian text in the 1800s and has literally been reprinted hundreds of times. In 1646, Diodati put to press his last work, the French Psalms in rhyme. Diodati died in 1649, leaving behind debt, a request that his sons print his Italian Psalms with the music included, and without really seeing how far his work would spread.

Diodati loved Geneva. He was presented with opportunities to live in Italy, France, and Holland; but he always went back home. Unlike him, his influence did not stay in Geneva. His 1607 Bible can be proven to have been used in the late stages of the KJV translating. William Bedell used Diodati’s 1607 as one of his sources when he prepared the Gaelic Old Testament in Ireland, and it was also the base of a Dutch Bible, which was printed twice in the early 1600s. His 1641 Bible was the base of a translation into Rumanscha. His notes found in his 1641 Bible were translated into English (1643) and became the best selling commentary in England in the 1600s. His notes were used in other Bibles in French, German, Dutch, and Hungarian. His Italian New Testament and the French Epistles were both printed in the latter half of the 1600s in Holland.

1700s

Diodati’s solitary rule of the Italian scriptures in the 1600s did not carry over to the same extent into the 1700s. There were two Italian Bibles and five New Testaments printed by Protestants in the 1700s. While Diodati’s work was heavily used in some and lightly used in others, his name was, for the most part, left out.

Of interest are the two Bibles. Erberg’s Bible from front to back is a curious edition. As per the text, he often began a chapter by using the text from the 1562 Italian Bible and after several chapters would switch and finish the chapter by using Diodati’s text. In the Old Testament, he used Diodati’s 1607, while for the New Testament, he used the recently printed 1702, which was a slight modernization of Diodati’s 1641 text. About 76% of the text is Diodati. A portion of the extant copies include a preface wherein Malermi, Brucioli, and Diodati are all recognized for their work on the Italian Bible. In about a quarter of those, Diodati’s name was left out. The last Bible was done by Giovanni David Muller in 1744. He claimed to have made, “a very correct and exact reprint of the translation of the famous Giovanni Diodati, which (as well as for the accuracy of the text, and the beauty of the style) has always been approved, and applauded from all the readers….” So it was that the last Protestant version of the 1700s claimed Diodati’s name as King of the Italian Bibles.

1800s

The 1800s started out similar to the 1700s. A revision of Diodati’s 1607 New Testament was made without his name appearing on it in 1803. In 1808, the British Foreign Bible Society printed their first Italian Scripture, which was a New Testament copied from the previous 1803 edition. In 1811, this was edited and published by the BFBS. In 1812 at Basle, a New Testament was printed based on Diodati’s 1665 New Testament. However, from 1819-1823, three Bibles were printed, which sealed Diodati’s 1641 text as the best Italian version and the one that would be used and reprinted for over 200 years. The first portion of Diodati’s work to actually be printed in Italy came in 1849 with the printing of his New Testament.

During the 1800s, the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge was more loose with the text and often printed edited editions, including the Bibbia Guicciardino (1855), which for the first time included many critical text readings. Near the end of the 1800s, two editions became the standard Diodati text: 1885 and 1894. From the late 1800s to today, these two editions continue to be printed.

1900s

In the early 1900s, John Luzzi completely revised Diodati’s text and printed it under his own Bible Society ‘Fides e Amor.’ He later become head of a committee, which published the Riveduta through the British Foreign and Bible Society. Many Christian churches in Italy left Diodati’s text and started using the Riveduta. In the late 1900s, a new edition called the Nuova Diodati was published, which carries some slight resemblance to Didoati’s text, although certainly not dedicated to it, and most likely based based on the Riveduta and revised using Diodati’s text and that of the CEI.

A brief digital history of the Italian Bible concentrating on the version of Giovanni Diodati.

After following the link, some of them will be available to download.

August 1471 The first Bible printed in Italian. Nicolo Malermi was the translator, who translated from the Latin Vulgate. Vol. 1, Vol. 2

- more versions from 1471 to 1600Second printed copy of the Italian Bible, 1471, based on some Italian manuscripts and the recently printed edition by Malermi.

1477 Malermi version.

1490 Malermi version.

1494 Malermi version.

1507 Malermi version.

1517 Malermi version.

1530 First New Testament translated from Greek by Antonio Brucioli.

1532 First Bible translated from Hebrew & Greek by Antonio Brucioli.

1536 Revision of Brucioli’s New Testament by Zaccheria da Firenze.

1538 Revision of Brucioli’s work by Santi Marmochino.

1538 Brucioli New Testament.

1538 Brucioli Bible.

1539 Brucioli Bible.

1539 Brucioli New Testament.

1540 Brucioli Bible Volume 1.

1541 revised Brucioli Bible.

1541 Malermi Bible.

1542 Zaccheria da Firenze New Testament.

1544 Brucioli New Testament.

1545 revised Brucioli New Testament.

1546 revised Marmochino Bible.

1546 Malermi Bible.

1546 Brucioli New Testament.

1547 Brucioli New Testament.

1549 Brucioli New Testament.

1550 Brucioli New Testament.

1551 Brucioli New Testament printed by Francesco Rocca.

1551 Brucioli New Testament printed by Gio. Grifio.

1551 New Testament revision of Brucioli’s by Massimo Theofilo.

1552 Brucioli Bible.

1552 Brucioli New Testament.

1553 Brucioli New Testament

1555 Crispin revised Brucioli’s New Testament.

1555 Giovan Luigi Paschale’s copy of Crispin’s New Testament.

1556 Teofilo New Testament.

1558 Burcioli New Testament Vol. 1, Vol. 2

1558 Malermi Bible.

1560 Revision of Paschale’s New Testament with Beza’s help.

1562 Brucioli’s Old Testament, Theofilo’s New Testament revised by Rustici and printed by Durone.

1562 Brucioli’s Old Testament, Paschale’s New Testament revised by Rustici and printed by Durone.

1566 Malermi Bible.

1567 Malermi Bible.

1576 New Testament based on Theofilo.

1596 New Testament based on Paschale.

1599 Polyglott New Testament (Italian follows 1562 Paschale edition).

click here to close

For those who use e-Sword Bible software, this download allows you to search and read some parts of Diodati’s 1607 Bible. eSword is free (donations are recommended) to download and use on computers. For Ipads there is a small charge, but very minimal in comparison to the value.

This document contains most of the New Testament except for Matthew and Luke. It also contains a few of the Minor Prophets and some Psalms.

Download files:

Windows

Mac

To install on Windows you can download the e-Sword Module Installer.

Or, if you are somewhat familiar with where you can access your computer’s drives; you can open your operating drive (normally C:). Then find the e-Sword folder (usually in a folder including the name “Program Files”). Once you open the folder labeled “eSword” you simply copy and past the unzipped file into the folder and reopen the e-Sword program. Your new Bible module will be installed.

For information on installing on a Mac; check out this article.

For information on installing on an Ipad; check out this article.

click here to close

1608 Diodati New Testament.

1609 20 Psalms paraphrased by Diodati.

1625 German Bible based on Diodati (reprint from 1632.)

1626 Book of Job in French.

1628 25 Psalms paraphrased.

1631 Diodati paraphrased Psalms.

1637 Ecclesiastes and Song of Solomon in French.

1638 Books of Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon in French.

1640/41 Revised second edition of Diodati’s Italian Bible.

This document was made from an OCR scan, and the English is a bit old, but most everything is understandable.

Download files:

Windows

Mac

To install on Windows you can download the e-Sword Module Installer.

Or, if you are somewhat familiar with where you can access your computer’s drives; you can open your operating drive (normally C:). Then find the e-Sword folder (usually in a folder including the name “Program Files”). Once you open the folder labeled “eSword” you simply copy and past the unzipped file into the folder and reopen the e-Sword program. Your new Commentary module will be installed.

For information on installing on a Mac; check out this article.

For information on installing on an Ipad; check out this article.

click here to close

1644 French Bible translated by Diodati

1646 Diodati French Psalms

1648 Second edition of Diodati’s English Annotations.

-1649 The death of Giovanni Diodati.

1664 Psalms

1665 Diodati’s New Testament.

1665 French Epistles

1667 French Epistles

1679 Swiss Rumanscha Version based on Diodati’s Italian Bible.

1700-1800

1702 New Testament. This is a revised edition of Diodati’s 1641 text by Christoph H. Freiesleben.

1709 New Testament. This is a revised edition of Paschale’s 1560/96 text by Giovanni Lucio Patrono and Giovanni Battista Friz.

1710 New Testament. This is a revised edition of the 1702 New Testament by David Guessner.

1711 New Testament. This is a second emission of that which was printed in 1702.

1711-12 New Testament. This is a revised edition of Brucioli’s old text done by Matteo Berlando della Lega and Jacopo Filippo Ravizza. Volume 1. Volume 2. Other editions show the date 1715, 1719, 1729 and 1735.

1711-13 Bible. This text follows 1562 Paschale for some chapters, and for the others it follows the 1607 Diodati for the Old Testament and 1702 for the New Testament. About 76% of the text comes from Diodati. It is revised by Mattia d’Erberg.

–1711 First emission..

–1712 Second emission of the same, Nuremberg.

–1712 Second emission of the same, Cologna.

–1713 Third emission of the same

1743 New Testament. This text follows the 1711-12 edition with revision done by Giovan Gotlobbe Glicchio.

1744 Bible. This follows the 1641 Diodati text with revision done by Giovanni David Muller.

1757 Second emission of the same text as the 1744.

1769 First edition Martini New Testament. Based on Latin Vulgate.

1800-1900

1803 Diodati New Testament. The text is based on 1607.

1808 The first edition of Diodati’s New Testament published by the SBBF. The text follows that of the 1803 printing.

1812 Diodati New Testament. The text seems to be based on Diodati’s 1665.

1813 Diodati New Testament. Second emission of the 1811 New Testament which was based on the 1808 with some revisions.

1816 Diodati New Testament. Third emission of the same text as 1811 and 1813.

1819 Diodati’s Bible. The text follows Diodati’s 1641 revised by Giambattista Ronaldi.

1822 SBBF Diodati Bible. The text follows Diodati’s 1641.

– The books of the apocrypha were no longer published with the Diodati Bible.

1825 Diodati Bible printed by Bagster.

1827 Diodati Bible printed by Bagster.

1830 Diodati Bible printed by Watts.

1835 Diodati Bible printed by Watts.

1836 Diodati New Testament printed by Dowall.

1841 Diodati Bible printed by Watts.

1844 Diodati Bible printed by Watts.

1845 Diodati Bible printed by Bagster.

1846 Diodati New Testament printed by Watts.

1846 Diodati’s Gospels with notes by Francesco Lamennais.

1846 SBBF Diodati Bible.

1848 Diodati New Testament printed by Watts.

1848 Diodati Bible.

1849 The first edition printed in Italy by Italians.

1850 Diodati’s Old Testament printed by Gilbert and Rivington.

1850 Diodati Bible printed by Spottiswoode.

1850 Diodati Bible printed by Watts.

1850 Diodati New Testament printed by Guglielmo Watts.

1854 Diodati Bible revised by Salvatore Ferretti.

1855 Diodati Bible.

1855 Diodati Bible revised by Piero Guicciardini and G. Walker.

1856 Diodati Bible.

1858 Diodati New Testament published by the S.P.C.K.

1858 Diodati New Testament printed by Spottiswoode.

1858 SPCK Diodati New Testament.

1861 Diodati Bible.

1861 Diodati New Testament.

1862 Diodati New Testament printed by Watts.

1862 SBBF Diodati Bible.

1862 Diodati New Testament printed by Clowes.

1862 Diodati Bible published by Claudiana.

1863 Diodati New Testament.

1864 Diodati Bible.

1864 Diodati Psalms.

1865 SBBF Diodati New Testament.

1866 SBBF Diodati New Testament.

1867 SBBF Diodati Bible.

1867 SPCK Diodati’s book of Acts.

1867 SPCK Diodati’s Gospel of Luke.

1867 SPCK Diodati’s Gospel of Mark.

1867 SPCK Diodati’s New Testament published by Claudiana.

1871 The first Diodati published in “free” Rome.

1872 Diodati’s New Testament revised by Italian Bible Society.

1872 SBBF Diodati New Testament.

1873 DSS Diodati New Testament.

1874 ABS Diodati New Testament.

1874 SBBF Diodati Bible.

1875 Pulpit Edition by the Italian Bible Society.

1875 SBBF Diodati Bible.

1876 SBBF Diodati New Testament.

1877 SBBF Diodati New Testament.

1877 SBBF Diodati Bible.

1885 DSS Diodati Bible.

1888 SBBF Diodati Bible.

1889 ABS Diodati New Testament.

1891 ABS Diodati New Testament.

For those who use e-Sword Bible software, this download allows you to search and read this revision of Diodati’s Bible. eSword is free (donations are recommended) to download and use on computers. For Ipads there is a small charge, but very minimal in comparison to the value.

Download files:

Windows

Mac

To install on Windows you can download the e-Sword Module Installer.

Or, if you are somewhat familiar with where you can access your computer’s drives; you can open your operating drive (normally C:). Then find the e-Sword folder (usually in a folder including the name “Program Files”). Once you open the folder labeled “eSword” you simply copy and past the unzipped file into the folder and reopen the e-Sword program. Your new Bible module will be installed.

For information on installing on a Mac; check out this article.

For information on installing on an Ipad; check out this article.

click here to close

1894 ABS Diodati New Testament.

1896 DSS Diodati New Testament.

1896 ABS Diodati New Testament.

1903 DSS Diodati Bible.

1906 ABS Diodati New Testament.

1910 ABS Diodati Bible.

1910 ABS Diodati New Testament with English KJV parallel.

1911 ABS Diodati New Testament with English KJV parallel.

1912 ABS Diodati Bible.

1986-87 Nuova Diodati Gospels and Acts by La Buona Novella.

1991 La Buona Novella printed the New Diodati, which was a revision of the Riveduta with some use of Diodati and the New Testament based on the Textus Receptus.

2003 Nuova Diodati revision.

Historical Fiction concerning Jean Léger and his Diodati Bible.

Jean [John] Léger somberly embraced each one of his children. Starting at the youngest, who was held in his mother’s arms, he wrapped his arms around each one individually. From slightly behind their ears, he whispered, “Je t’aime.” Each embrace was firm and brief, just the perfect amount of love and security. As he passed from child to child, he prayed in his spirit for God’s protection to be upon his family in this particular journey. Even though he seemed outwardly to have such resounding faith, a bit of doubt slipped into his silent words to God, “. . . and in case I don’t survive . . .” He caught himself and stopped his mind from continuing. Finally he reached his eldest child, who would be the oldest of eleven children to survive birth. He gave him a stern reminder to support his mother and aid her as much as possible with the other children and the trip in general. Then he passionately held his wife, Marie Pellenc, and kissed her. They had heard stories of former generations but never realized, when they got married 15 years previous, that it would happen to them. Jean Léger was not soft; neither did he imagine to show any lack of faith to his wife, although they both knew the real possibilities that this might be the last time they would see each other. Jean gave his family into the hands of the Eternal One and watched as they trekked through the snow, over the mountain crest, and out of sight.

The date was April 22, 1655, and Marquess of Pianezza was leading an army of some 4,000 soldiers from Italy, France, and Ireland through the Waldensian valleys of Piedmont, Italy. Before sending his family over the mountains of Angrogna, Léger and his family gathered their meager belongings from the small house they occupied. There was a slight rush to their escape, and certainly more time would have been useful. His eyes caught a couple of piles of old books and documents stacked together on a wooden shelf in the corner. His mind struggled to grasp the future of these precious works. For almost 10 years, Léger had been collecting items from the valleys concerning the heritage of his faith. He had archives, letters, some manuscript Bibles, an some in print, and other irreplaceable records, some of which were hundreds of years old. He had been authorized by a Waldensian Synod and, with that authority, borrowed these items from their owners. There wasn’t much he could now but apologize to them . . . if they survived. Outside he heard a distant noise that shook his mind from the dilemma. He quickly grabbed one book from the piles and put it into his satchel. There was no mistake in his choice. The noise, the rush, the fear did not cause him to error. It was clear which book was the most important to him. Now that he had saved his book, it was time to save his family.

While Léger desired to go with his family, he had obligations to attend to before they could be reunited. After his family headed over the mountains, down a mule path, and into the most isolated Waldensian community, Pra del Torno, Léger went around the mountain the other way to rendezvous with the men of the community where he was pastoring. From their vantage point at the north of the Pellice Valley, they could see down into the whole valley. Not all the men were there. Some of the older and more stubborn members couldn’t bear the idea of giving up the land and homes, which had been in their families for generations. There were also others who had purchased theirs with their own money and had similar apprehensions. As Léger and his men looked southward over the valley, they could faintly see the destruction of Saint John quite a distance away. Smoke from the torched houses darkened the sky. Léger knew all his treasures were gone. The soldiers were easily overtaking the remaining residents. Survivors were abused, tortured, burned, and killed. Their screams spread like a heavy fog. At times it seemed that the men on the hillside could recognize the voices, even at such a distance. The men’s minds each wondered if their assumption was right, but no one dared say what they were thinking. The towns of Saint John, Torre Pellice, and many others were a total loss. The army was stronger than the resistance had hoped, and it was time for the men watching from above to flee before that would no longer be an option.

The men prayed together and departed to find their families; some had left them in their homes a distance from the fighting, and others had already sent them on the trail as Léger had done. Léger himself did as the other men. He followed his family down to Pra del Torno, which was often a refuge to fleeing Waldensians. However, at his arrival, he found that his wife and children had continued on without him. It wasn’t much of a shock, as he had advised them to do so if he did not promptly arrive.

Pra del Torno was experiencing more traffic than anyone alive could remember. Léger recognized some close friends from the Italian-speaking community of Chabas, Antonio and Sarah Paschale. He compassionately greeted them and gave them his ear. They were shaking and obviously frightened. Léger wanted to leave quickly, but he knew this couple could use some of his time. After listening to them for a short while, Léger removed the book from his satchel and flipped through its pages to several familiar spots. He pointed out some lines and read them to the couple. He was as brief as the situation required but still thought his efforts in the end were insufficient. But maybe this would be the drop of honey they needed. The Paschales had been aided before by Léger’s spiritual guidance, but today it was his time which they were most genuinely grateful for and comforted by, not necessarily his words. Putting the precious volume back into his bag, he gave his farewell to his friends. The pastor of Angrogna, Jean Michelin, had just arrived and began helping Léger. They stood outside a small, abandoned house on the main path through town and ministered to the refuges who were passing through. The clock was always ticking in the back of their minds, and after several hours, Michelin and Léger departed together.

They climbed the steep slopes upward. As the sun started to set, it grew colder. The men thought they might have stayed a bit too long at Pra del Torno, but there was no use in talking about the past if it couldn’t help the present. They knew the Frasche family, who lived in the area, but it was too late to disturb them. Surely they could find some form of shelter nearby. The Frasches had been Waldensian and were very compassionate towards them, but for fear of their lives, they had recently recanted and become a part of the Catholic Church. There were no grudges on either side in times like these. In fact, the Frasche family had allowed several Waldensian families, who were forced to flee their homes in the lower valleys, to stay with them, but now even this far out, it was not safe to house them. As the pastors had expected, they found a stable nearby the main house where they could shelter for the night. Both men were cold, hungry, and desirous to see their families. They ate the snow for food, but in reality, the cold was more severe than their hunger. Their thick clothes were soaking wet from a mix of internal perspiration and external precipitation. No matter how much they wanted to have a fire, it would be a dead giveaway; they would have to suffer.

The place was uncomfortable, but as tired as they men were, they didn’t notice the sun starting to rise the next morning. They were awakened by the startled Susanne Frasche, the mother of the home. She was a short, thin lady in her mid-thirties. Her dark, tattered hair and complexion told of the type of life she was living. She was a woman of the hills, strong and kind. She had come out in the morning to get some firewood and noticed the men. Thankfully, she held in her fright. Realizing who they were, she woke them from their sleep. She would have rather gone and gotten her husband who was inside tending to the fire but was afraid it might attract too much attention. The men were startled from their sleep. It took a moment for their eyes to open and see in the dim lighting who was standing before them. Michilen recognized Susanne first and attempted to stand to his feet, but Susanne quickly motioned for him to stay down—from fear, to joy, to fear again. Someone else was there besides the Frasche family. She got down and whispered to them that soldiers were in a cottage nearby. She recommended they leave out toward the west before going farther north. The men thanked her greatly and prepared themselves for the journey.

Léger’s neck was a bit sore from an awkward night’s sleep. He had thought about using his tote, with the book in it as a pillow, but afterwards decided it wouldn’t be best to do so. Even with the slight pain to his neck, he looked at his book with satisfaction that he hadn’t done as he had contemplated. Wrapping it tightly on his back, the two men crawled through the snow on their stomachs. They went in single file so as to make as small a trail as possible. It wasn’t fast, but the sun was starting to cast shadows, and it would be better to stay hidden and crawl slowly than to take the chance of being seen.

The soldiers took some joy in ridding the land of what they called “beasts of Hell,” and so they had pride in the depth of their work. The Waldensians were scattered throughout the hills, and the snow was their traitor. As the soldiers awoke and took another sip of wine from their flasks, they headed out to hunt again. They had searched the immediate area the night before but decided to do so once more. As they came around the back of the stable outside of the Frasche house, they noticed tracks flowing into the distance. All good hunters know how to tell which animal left what type of track. The tracks they spotted were obviously those made by man. The two pastors were just barely out of sight. The soldiers thought the marks appeared to be made by just one man, and they were not convinced on how long ago that was. The youngest of them argued that the marks couldn’t have been more than just a few minutes old or at the most an hour. The others thought it would be a waste to chase after one man who might be long gone by then. The majority won; however, the young man wasn’t content without first firing several rounds into the direction of the tracts. The other soldiers just laughed and mocked him, saying that he was hunting rabbit spirits. The pastors literally heard the bullets fly over their heads, but they had gotten away.

That entire day they climbed, hid, crawled, starved, froze, and prayed; but by nightfall, they had made it to the relative safety of Pramollo, where they stayed at the house of Barthelemy Jahier. Jahier was a born leader and a captain of the resistance. He was barely literate, but that didn’t change his natural skills. It would be two whole days before Léger would finally cross over the Chisone River and be reunited with his family, but it was here at Pramollo where he knew he had gotten away. Again he pulled out his book. It was fairly new, having been printed just 15 years before. He had bought it with his own money and spent hours in it, making notes throughout its pages. It was a Bible; the Italian version by Giovanni Diodati. He borrowed a quill from Jahier and wrote on the front-end sheet, “This holy Bible is the only treasure which, of all my goods, I was able to rescue from the horrible massacres, and unparalleled destructions which the court of Turin put in execution, in the valleys of Piedmont, in 1655, and for this reason (besides that there are in it many small remarks in my own handwriting) I recommend and command my children to preserve it as a most valuable relic, and to transmit it, from hand to hand, to their posterity. –John Léger, Pastor.”